The proposal

SeaChange comprises of four components.

Replace the vast majority of public assistance programs with a monthly guaranteed income payment (aka, Universal Basic Income) of $1,000 per adult and $300 per child to all but the top 2.5% of income earners.

Implement a system of universal health care that guarantees all citizens and legal permanent residents (LPRs) access to high-quality, truly affordable care.

Replace all personal and corporate income taxes with a consumption (national sales) tax of 26%.

Restructure and reduce payroll taxes.

Universal Basic Income

Replace Public Assistance and Unemployment Compensation Programs with a Monthly Guaranteed Income Payment Made to Nearly All Citizens and Legal Permanent Residents

The current system of public assistance programs is burdensome to participants, cost inefficient to manage and creates significant disincentives for working. Programs of note include the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children/WIC, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program/SNAP, subsidized housing, and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families/TANF, among others. Recipients of these benefits can lose benefits once they start receiving income from a newly attained job. Also, according to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), effective marginal tax rates for increases in income of just several thousand dollars can reach 95% even at income as low as $23,000 [1].

On top of that, stigma exists around receiving public assistance (aka “welfare”). This combined with the burden of applying for and remaining on the program results in a portion of those who qualify for assistance not applying to receive it. As just one example, roughly 15% of those eligible for SNAP (food stamps) do not apply to receive it [2].

However, despite the personal costs involved, 21.3% of U.S. residents receive one or more forms of public assistance in a given month [3].

The SeaChange plan proposes to eliminate the vast majority of public assistance programs and replace them with a monthly payment made to almost all U.S. citizens and LPRs regardless of income. The standard monthly payment would be $1000 for adults and $300 for children.

With SeaChange, a family of four would be guaranteed an income of $31,200 a year.

The amount of the payment would gradually diminish at a rate of $100 for every $1,000 per month earned over $7,000 per month resulting in no payments being made to individuals who earn $17,000 or more per month (i.e. $204,000+ per year, the top 2.5% of income earners).

These payments will be made only to those residing in the U.S. for 180 days or more in a given year. Payments would be made monthly based on a semi-annual application process during which individuals state their income for the past six months under oath. This application process will be able to be completed either online and in-person.

The proposed monthly payment well exceeds the median monthly benefit across all public assistance programs of $404 per individual [3]. Median monthly Supplemental Security Income (SSI) payments, administered by the Social Security program, are highest ($698) but apply to only a small fraction (3%) of the population and would not be affected by this proposal (i.e. we are not proposing to eliminate SSI since it is both means and disability-based) [3].

Universal Health Care

Implement a Single-Payer System of Universal Health Care

The Patient Protection and Affordable Health Care Act of 2010 (PPACA) promised to provide all U.S. citizens with access to quality, affordable care. Even though the legislation provides key protections, it fails to live up to its promise. These key protections were designed to ensure that anyone who wanted insurance could get it, and that no one would be threatened with bankruptcy due to serious medical conditions. These include: caps on annual out-of-pocket payments, removing lifetime coverage limits, limiting carriers’ ability to rescind insurance and banning coverage exclusions for pre-existing conditions, and providing a tax credit for insured persons in lower-income brackets. The failure of the legislation’s promise is not due so much to fundamental issues with the original legislation, as with decisions by Congress in the years after PPACA was enacted to reduce (and most recently cease entirely) making cost-sharing payments to insurers who take on higher portions of sick, high-cost patients.

Not surprisingly this legislative decision increases insurer risk, resulting in rising premium costs and/or cost-sharing requirements. Between 2017 and 2018, the unsubsidized premium for the lowest-cost bronze plan increased 17% on average across all counties in the U.S. while the lowest-cost silver plan increased on average 32% [4]. Using marketplace plan data from 49 states and the District of Columbia, the Commonwealth Fund found that of the seven types of cost-sharing examined only one decreased between 2015 and 2016 and three increased significantly across all plans. Out-of-pocket limits increased by 7%; annual deductibles, by 10%; and copayments for drugs increased by 14%. For Bronze plans, specifically, the annual deductible increased 10.4%; copayments for specialty visits rose 26.1%; and copayments for non-preferred-brand drugs rose 16% [5].

Individuals covered by employer health insurance have experienced even greater increases in cost-sharing with more employers moving to high-deductible plans. Since 2005, the average deductible on workplace plans has increased on average 15 percent per year; from 2014 to 2015, the average deductible increased by approximately 9% [5].

For large employer plans, out-of-pocket costs (deductibles, copayments and coinsurance) rose by 66% between 2005 and 2015 (from $469 to $778 annually) across all covered employees.

Those who are high health spenders (top 15% who together account for 75% of total benefit costs) had significantly higher out-of-pocket costs - $2,765 on average in 2015 [6].

These out-of-pocket costs do not include premium sharing. Annual premiums for employer-sponsored family plans were $18,764 on average in 2017 with workers paying $5,714 (30%) of the premium. Covered workers contributed 18% of the premium totals for single coverage and a whopping 31% for family coverage in 2017, on average [7].

In sum, the PPACA promised to make health care more accessible for all Americans. While some have seen improved access through reduced costs (in particular lower income populations who receive tax credits that reduce or completely eliminate premium costs), a substantial portion of the U.S. population has not and, in fact, have taken on greater portions of ever-increasing health care costs.

Those who live at or below 100% of the federal poverty line (FPL) are generally not eligible for tax credits because it is assumed they qualify for Medicaid. While 36 states and the District of Columbia chose to expand Medicaid to cover most low-income adults up to 138% of the FPL, 14 have not done so [8]. In general (Tennessee and Wisconsin being notable exceptions), states choosing not to expand Medicaid have extremely limited policies regarding Medicaid coverage on average covering jobless adults only up to 43% FPL and working adults up to 61% FPL (author’s own data). Thus, in 24% of states, a significant portion of adults with low incomes do not qualify for either subsidized private health insurance through the health insurance marketplace or for Medicaid coverage leaving them effectively without access to insurance coverage.

On top of this disjointed system that pushes an ever increasing portion of health care costs onto individuals thereby reducing access, the U.S. spends more per capita on health care while also achieving worse health outcomes.

Specifically, we pay two-and-a-half times the average of Organisation for Economic Co- operation and Development (OECD) member countries, and more than twice that of many other high income, developed countries per capita for care [9]. The underlying causes are clear: higher prices and massive inefficiencies in our disparate systems of care.

We already have two single-payer systems at the federal level: Medicare and the Veterans Health Administration. At the state-level, Maryland has an all-payer system and Vermont approved a single-payer system in 2011, with 2015 being the first full year of operation.

We propose a model similar to Medicare.

Specifically, a core set of benefits would be guaranteed to all Americans that would be premium free and have very low (or no) copays and no deductible requirements. This results in a huge cost savings to individual workers. Individuals who need or want a higher level of coverage can opt to pay a premium for coverage above and beyond the core coverage.

All other industrialized nations have successfully constrained health care pricing and costs through either a single-payer or coordinated “all-payer” payment system [10]. Multiple studies credibly estimate that excess costs make up 30% of total health care spending in the U.S. [10].

Multiple sources estimate that transitioning to a single payer system would reduce U.S. health care expenditures by 12-20% in administrative costs alone [10]. Additional savings will come from reduced fraud and abuse, integration of the delivery system resulting in more efficient care, and streamlining of payment systems. An all-payer system would reduce health care expenditures by between 5.9% and 12.6% [11-13].

To sum it up, our current system of health care is disjointed, inefficient and does not provide quality, affordable care to all taxpayers. The time to act is now and the obvious solution is one of guaranteed access to care that is affordable, treats access to basic health care as a right, and is administered by a single body.

Replace All Personal and Corporate Income Taxes with a Consumption Tax (excluding necessary expenditures)

The current U.S. income tax system is a leaky sieve. The country currently loses approximately $189 billion in corporate tax revenue annually through entirely legal avoidance maneuvers involving profit shifting to foreign tax havens [14].

In addition, the Internal Revenue Service estimates that $458 billion in personal income tax is not paid voluntarily and in a timely manner, an amount equal to 18.3% of personal income tax revenue owed. The IRS estimates that it ultimately is able to collect $52 billion of this total, leaving $406 billion in personal income tax revenue lost to tax evasion each year [15].

Shifting to a system that levies tax at the point of consumption would bring more money back into the U.S. economy to be spent and invested. It would also allow every citizen or LPR to share in supporting the Federal Government. Also, any non-legal resident would also be paying this tax without receiving the benefits covered here such as healthcare and monthly basic income.

Specifically, we propose a 26% (exclusive) tax (aka “FairTax”) be levied on the sale of new final goods and services purchased in the United States and final goods purchased in other countries for consumption in the United States.

This is in addition to any state or local sales tax. The proposed tax base is broader than what is currently taxed; however, necessary expenditures that make up the bulk of household budgets for lower income populations (eg. rent, groceries) will not be taxed.

Under the current proposal, all employers would now pay a tax on final products and services purchased, a departure from current law, which exempts non-profits from sales tax. While this will increase consumption costs, the SeaChange proposal provides cost savings afforded to all employer entities including restructuring of payroll taxes and elimination of the need to provide healthcare coverage for employees. (Additional detail is provided in the following section.)

The proposed tax base includes taxing government consumption.

This provision is necessary in order to equalize personal and government consumption. Failing to do so would make government consumption expenditures artificially cheap (compared to private consumption), and would lead to the provision of some goods and services migrating from the private sector to the government sector [16].

For details on what would be taxed and the estimated revenue generated, see Technical Appendix A. As part of this proposal, local and state entities would receive 0.25% of consumption tax revenues as payment for managing the collection of said taxes.

Payroll Tax Reform

Currently payroll taxes are levied on employee wages at a rate of 7.65% to be allocated to paying for Social Security and Medicare for older adults. However, employer-funding of health care is a bulwark of the current healthcare system that aligns with the values and culture in this country. Further, with the elimination of all corporate and individual income tax, companies need to contribute to the balancing of the budget.

We propose to levy a flat payroll tax equivalent to $700 per month per full-time employee and $350 per month for part-time employees.

Additionally, for those who are self-employed, we propose levying an additional 4% tax (on top of the 15.3% tax currently paid) to align it with the changes in employer payroll tax policy and to help cover the costs of providing universal health care coverage and the elimination of income tax.

Effects on Federal Budget

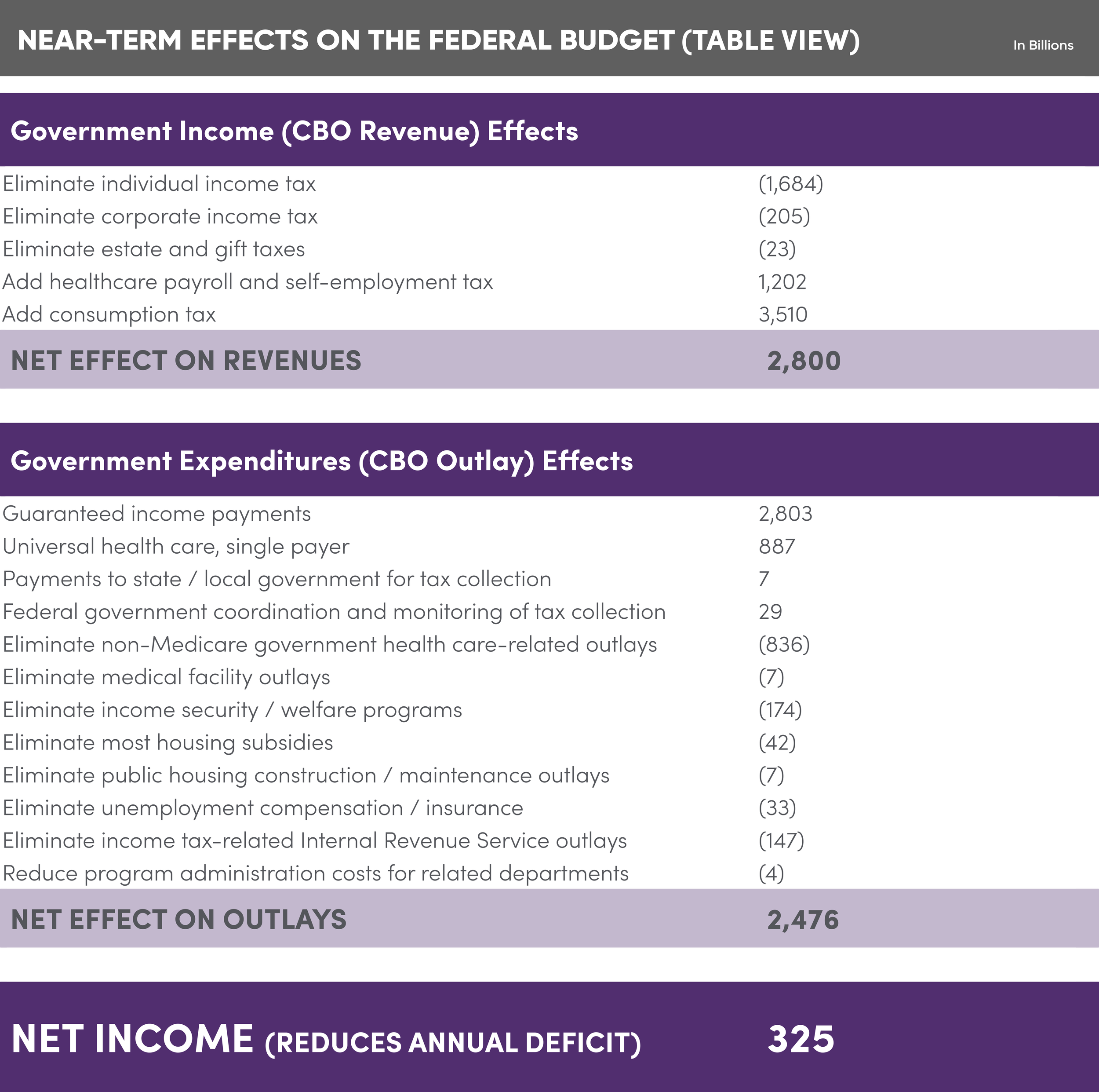

The following illustration details the fiscal impact of the policy changes detailed above on the short-term federal budget. The federal deficit averaged $691 billion annually between 2015 and 2019, and was $984 billion in 2019.

Through increased tax collection and projected increases in employment and consumption, the policy changes proposed would result in reducing the annual deficit by an estimated $325 billion per year [17].

It is important to note that consumption taxes will be charged to all purchasers of final goods and services, regardless of residential status (eg. non-legal residents and temporary visitors from other countries), but that universal health care and guaranteed income benefits will only apply to U.S. citizens and LPRs. For details on how the various line items were estimated, see Technical Appendix B.

As a note: under a system of universal health care, the Medicare portion of payroll taxes for both employers and employees will become obsolete. However, due to difficulties in estimating the federal government’s portion of total Medicare expenditures, we did not include this change in the current model. Thus, the universal health care line item only includes estimated health care costs for those ages 0 to 64.

Table View:

Effects on Key Groups of Americans

Effects on Key Groups of Americans

SeaChange proposes fundamental modifications in how the federal government generates revenue, ensures that taxpayers can access the healthcare they need without fearing financial ruin, and provides a guaranteed monthly income payment to all but the top 2.5% on income-earning Americans. As such, an obvious question policy-makers will ask themselves is “how will these policies, together, affect key constituencies?”

This section discusses the anticipated effects on some of these constituencies.

Veterans

Those who have served in the military have worse health than their counterparts who are similarly aged. Specifically, veterans have higher rates of arthritis, cancer, cardiovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and chronic pain [18]. Members of the military access medical care through the Veteran’s Administration (VA) health care system. The issues with the VA healthcare system are many and well-documented [19-22]. Veterans still experience long wait times, bureaucratic hurdles and unsafe conditions, despite billions having been spent on the problems. The nature of the problem is not going to go away due largely to poor economies of scale. The VA owns more than 6,000 buildings and leases another 1,500 that are dispersed across the country. On average they were built in 1960, five times older than most not-for-profit medical facilities and many are reportedly crumbling and underutilized [23]. SeaChange’s proposal to provide universal health care to all includes veterans, eliminating the VA health care system entirely. In so doing, it would resolve the health care access issues faced by military service men and women.

Americans with Low Income

Americans with low income, defined for these purposes as those earning less than 133% of the federal poverty line (FPL) per year (eg. $16,146 annual income for a single-person household, $21,892 for two-people and $33,383 for a 4-person household), will experience a direct financial benefit from the proposed policies. Currently, approximately 74% of individuals living at or below 100% FPL participate in one or more of the major public assistance programs for one or more months each year; and the vast majority depend upon the programs long-term (i.e. over one year) to make ends meet [3]. This includes almost 40% of children under 18 years of age [3]. The median combined monthly benefit received by those living in poverty was $449 between 2009 and 2012 [3].

The guaranteed monthly income payments to this group ($1,000 per adult and $300 per child) clearly exceed the median. In addition, these policies remove disincentives to work and are projected to increase labor demand, therefore positively affecting this segment of our society.

While the proposed consumption tax will impact the price people pay for goods and services, it does not tax necessities such as groceries and rent payments which make up a significant portion of monthly spending in low income households.

Households with low incomes spend a significantly higher portion of their before-tax income than higher income houses on necessities [24]. Technical Appendix C shows the estimated short-term effects of this policy on low income households of varying compositions and current assistance and monthly total income levels. What they demonstrate is that monthly purchasing power will likely increase regardless of current assistance level and household composition. (The analyses in Appendix C assumes that in single parent households with children, 50% of the guaranteed income payments designated to an absent parent are garnished for child support. In alternate analyses that dropped this assumption, the effects on purchasing power were smaller but remained positive for 96% of the household composition/public assistance level combinations). As data is not readily available on how government assistance is distributed across households, this proposal would benefit from further modeling in this area to better understand the impact of the policy on our most vulnerable residents.

The Middle Class

Tuerck and colleagues at the Beacon Hill Institute at Suffolk University estimated the effects of a FairTax policy on the lifetime utility by household income level. Lifetime utility is composed of the utility households get from consumption of goods, services and leisure. The policy the Beacon Hill group modeled included a 30% (exclusive) tax and a pre-bate equal to the amount of sales tax households living at the poverty line would pay [17]. Thus, their policy did not include the more generous monthly guaranteed income payments proposed here. Using Computable General Equilibrium modeling, they found that households earning between $10,000 and $149,999 (2006 dollars) would experience declines in utility for the first five years after implementation mostly due to choosing to increase time worked (and thereby reducing leisure time), but that five of seven income groups would experience a net positive change in lifetime utility.

Adjusting for our reduced tax on sales (26%), more restricted tax base, and the more generous monthly income payment would reduce these negative effects, and likely result in positive changes for some income groups (in particular those at lower income levels). In addition, the vast majority of the middle class will see reduction in health care costs with the introduction of universal health care coverage.

This, like the section above, is an area that would benefit from additional modeling that includes the effects of guaranteed income payments, universal health care, and the labor market effects of the recommended policy changes.

State Government

Currently state and local governments bring in over $2.74 trillion through a combination of taxes, charges and miscellaneous revenue to cover expenditures [25]. Across all states and localities, sale tax revenues account for almost one-fourth of this amount, while income and property taxes each account for another 20% [26].

The federal policy changes proposed would undoubtedly necessitate a shift in how states and local jurisdictions collect funds to cover operations.

Given the variation in how state and local government revenues are generated, there is no one easy and obvious answer. That said, some states and localities may choose to adjust their sales tax policies to align with the broader base of taxable items and services proposed in the current policy; doing so would allow them to reduce their sales tax rates. Too, the guaranteed income payments and elimination of federal income tax for individuals and corporations will almost certainly result in greater consumption, which itself will generate more revenues through sales tax.

In addition, the guaranteed income payment and universal health care components of the proposed policies will reduce state expenditures on social programs and Medicaid, reducing the level of revenues needed. State and local governments in 2018 spent approximately $600 billion on Medicaid, $20B on family assistance programs, $20B on other general assistance [27].

It is also quite possible that the guaranteed income payments will result in a greater demand for higher education and other services (eg. state parks) that are sources of state and local revenues.

Non-Profits

Under the current proposal, all employers including nonprofits would now pay a tax on final products and services purchased, a departure from current law, which exempts nonprofits from sales tax. While this will increase consumption costs, the SeaChange proposal provides cost savings afforded to all employer entities including restructuring of payroll taxes and elimination of the need to provide healthcare coverage for employees. In addition, it is well-recognized that individuals in the nonprofit sector can be under-paid relative to what they could earn in the for-profit sector. The general sentiment is that the low pay is made up for by feeling good about what you get up and do every day [28]. However, this only goes so far and can result in high-rates of staff turnover.

The guaranteed income payment included in SeaChange will allow nonprofit employees to do what they love and make ends meet.

Finally, it is likely that most nonprofits will also see increases in donations as more segments of society have extra money in their bank accounts each month.

The Business Sector

SeaChange is projected to be a net windfall for the business sector. As the Federal Budget Effects table in the previous section shows, it is anticipated that businesses will pay more, on average, in per employee taxes under the proposed plan. However, what is not included in this table is the $1,089.55 monthly health insurance premium that employers currently pay on average per worker, which amounts to 68% of the total premium costs [29]. Under the proposed policy, employers no longer need to provide medical benefits to employees (although they could certainly choose to provide extended coverage as a perk of employment). In addition, because all adults will now receive a $1,000 monthly income payment, unemployment compensation will be less necessary, reducing employer unemployment insurance costs (unemployment insurance may be purchased privately as a perquisite of employment). More importantly, corporate income taxes are also now eliminated, allowing businesses to increase capital expenditures, thus increasing productivity, or pay higher dividends, giving shareholders more money to spend. Moreover, it is projected that demand for most products and services will increase due to increased income in the pockets of most residents. Businesses will, like everyone else, pay a higher consumption tax on all final goods and services purchased, but overall this policy is projected to be a net-win for the business sector.

Intended/Unintended Consequences & Future Work

Beyond the impacts noted for specific sectors, we expect that other longer-term societal benefits would include: a) reduction in law enforcement costs related to crimes of extreme poverty and those related to tax evasion; b) increased investment in education (in particular, that which is aligned with the jobs market); c) increased entrepreneurism; d) increased capital available for investment in part due to the elimination of the capital gains tax; e) reductions in state and local government spending on assistance programs which may result in lower taxes, f) reductions in delinquent child support payments, and g) over time, decreased use of emergency rooms for ambulatory sensitive conditions which will further reduce health care costs. We also anticipate that this policy will result in shifting labor market demand. As one example, the need for tax accountants will be greatly diminished allowing their skills to be re-deployed to jobs that have a direct impact on business productivity. While we anticipate all of these impacts, we acknowledge that this proposal would benefit from others modeling what the magnitude of the effects is likely to be.

Similarly, our estimates of impact on personal consumption, gross domestic product, health care spending, etc. are drawn from the existing base of evidence. However this policy proposes a sea of changes, the joint effects of which would benefit from additional modeling. For example, what are the combined effects on consumption, savings, labor supply and demand, and gross domestic product of monthly guaranteed income payments and higher prices? The answer will likely vary by household composition and income level, and industry. Too, the timing of these effects may vary. For example Tuerck and colleagues, in modeling the economic impacts of a FairTax policy found that it would take a couple of years for consumption to increase as individuals choose to increase savings in the short-term [17].

Too, how will the labor market respond when per employee costs borne by employers fall? Some models indicate that labor supply will increase due to the removal of the double tax on income [17]. On the other hand, it is possible that some workers will choose to work less because they now have more income. The little evidence that exists on the labor market effects of guaranteed income payments (including of lottery winners) is that these payments have negligible impact on decisions to work. The projected impact on the future of work will most likely be due to a) earlier retirement by older residents, b) recipients deciding to use payments to fund additional education, and c) some reduction in the number of hours worked by those who can afford to do so [30, 31].

Finally, the current model assumes a single-payer system of universal health care is selected. It is not clear what the pathway to this solution is in the U.S. It would be useful to more thoroughly model the anticipated effects of both single-payer and multi-payer systems of universal health care.

Very little contained in this plan we call SeaChange is original. Instead, it’s a consolidation of a number of well thought-out and vetted programs, created by others, into a single platform. In an era of annual increases in government deficits and concerns about government spending, rising income inequality and levels of consumer debt, and bipartisan concerns about the rising costs of and reduced access to health care, a fundamental shift in the way our federal government operates must happen.

The foregoing report details a proposed set of policy changes the effects of which include improved access to health care, improved population health, reduced health care costs, and increased access to jobs while ensuring that all citizens and legal permanent residents of the U.S. share in the burden of supporting our federal government while having a guaranteed source of income to meet their basic needs. Importantly, it will also significantly reduce year-to-year deficit spending by our federal government and does so while eliminating all taxation on income.

The foregoing proposal is not a final product but rather an attempt to get the conversation started.

We realize adjustments will be made as some of the additional research and modeling outlined are completed, and others with differing view-points become engaged. We look forward to being a part of the conversation.

Confidence in federal government is at an all time low. Only 17% of Americans say they trust the government in Washington to do what is right. Low trust attitudes exist regardless of party lines with only 21% of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents and 14% of those who identify as Democrats or Democratic-leaning voters saying they can trust the government [32].

The time is now for policy-makers on both sides of the aisle to come together and take tangible steps toward addressing the issues that the U.S. populace cares about. Doing so is the only way to restore the public’s faith in our federal government. SeaChange is a policy designed for universal appeal.

So, what’s next?

As this updated proposal is re-released in the middle of a pandemic, there could not be a better time for serious conversations and actions towards renewed workability in this country. While clear in vision, obviously the systemic redesign proposed by SeaChange calls for bold leadership.

If you are a leader in academia, a think tank, government, business, community leadership or the media, I trust you may have reviewed the SeaChange proposal considering how it may complement or challenge your own initiatives.

The aim in publishing SeaChange is simple:

We offer the ideas and analysis for broad adoption, iteration and collaboration. If you are a change-maker—from anywhere across the spectrum—SeaChange earnestly invites your feedback, tough questions and opportunities to collaborate for the common goal of “an America as good as its promise”.